Culpability, Buckeye and Bridge of Sighs: Book Club Books Review and Craft Tips

Part of my ongoing series Reading as a Writer to study what resonates with me as a reader and what craft tips I learned as a writer—and how debut authors like me can hopefully position their work for book club success!

While I love snazzy books about bright lights and the big city (the novel I’m currently querying is very much this), my current work-in-progress is about a paper mill dynasty in Wisconsin and follows two characters who leave, and one who stays. Accordingly, I’ve been studying books that explore place, legacy, and the choice of staying versus leaving.

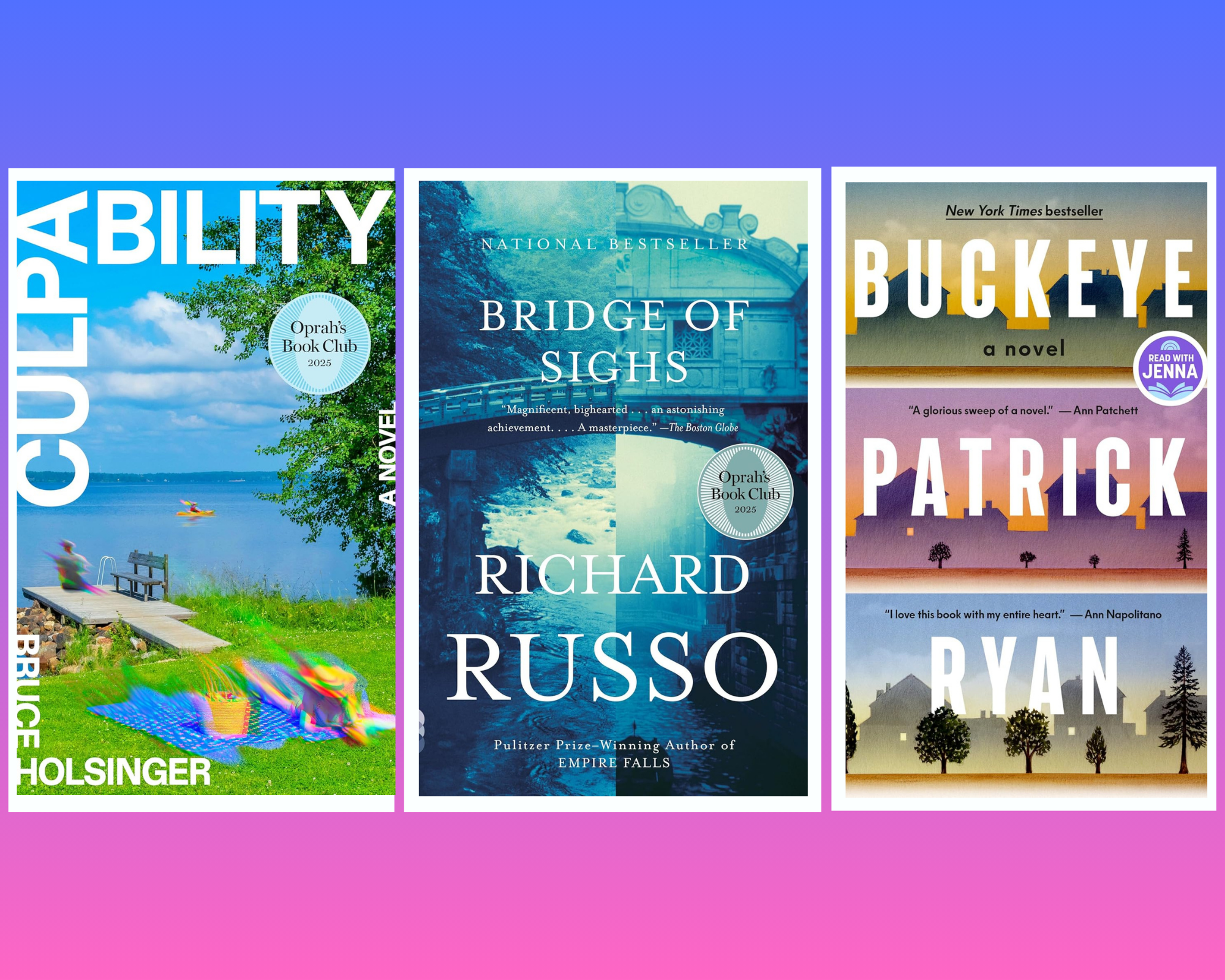

This past month, I dove into three celebrity book club picks that function as masterclasses in these exact themes: Richard Russo's Bridge of Sighs (Oprah August 2025 pick; published by Knopf), Patrick Ryan's Buckeye (Read with Jenna September 2025 pick; published by Random House), and Bruce Holsinger's Culpability (Oprah July 2025 pick; published by Spiegel & Grau). All three deploy innovative structure and multi-points-of-view to transform place into character. A perfect craft study for my work-in-progress.

Coincidentally—after studying so many upmarket books by women about women—this was my first time in a long time reading three male authors in succession! I enjoyed it!

Here's what I learned reading as a writer:

How Multi-POV Builds a World

Nearly every book club pick I've studied over the past year employs multiple point-of-view narrators, and these three are no exception. Not only is it fun for a reader, but it’s a technical way to show different angles of the same characters or place to create a multi-faceted view.

In Buckeye, we encounter a multi-generational chorus across 464 pages. The novel spans from WWII to the late twentieth century in small town Bonhomie, Ohio, following two families bound by a secret. By shifting POVs between characters like Cal, who works at his father-in-law's hardware store, and Margaret, an orphan who moves from the city as a young bride, along with their spouses and children, Ryan creates a panoramic view of the town's evolution. We see this fictional community through a wide-angle lens, watching secrets ripple across decades.

Richard Russo's Bridge of Sighs uses a dual-geography approach. This 550-page saga primarily covers half a century in Thomaston, New York and alternates POVs between two men who grew up as friends. The protagonist’s wife’s POV emerges later. We get Lou Lynch's first-person, nostalgic account of growing up in the blue-collar town—he’s a convenience store owner who adores his father, his family and his life. This sits in tension with the close-third-person, present-day perspective of Bobby Noonan, a tortured artist who fled to Venice and sees Thomaston and his own family through a far more unforgiving lens.

Bruce Holsinger's Culpability offers a completely contemporary vibe. Instead of a sweeping saga, it's a pressure-cooker. The story detonates when a family's self-driving car crashes, killing other drivers while the oldest son sat at the wheel. The novel's fragmented structure mirrors the family's disintegration: we rotate between protagonist Noah's raw perspective, his teenage daughter's chatbot conversations, excerpts from his wife Lorelei's book on AI ethics, and Congressional testimony. This collage of voices and media depicts a family—and a world—shattered into conflicting fragments.

The Inescapable Town: Setting as Moral Landscape

In Buckeye and Bridge of Sighs, the towns of Bonhomie, Ohio, and Thomaston, New York, aren't exactly thriving. Over fifty years, they face economic fluctuations—mostly decline for Thomaston, which is plagued by cancer clusters from the tannery's toxic runoff.

Yet the authors render these places without condescension. The past isn't merely inescapable; for some characters, they don't even wish to escape. These small towns function as extended family systems where everyone knows everyone's inheritance, everyone's shame. But what moved me most was how, even in these tight-knit communities, the characters still suffer from profound loneliness—the kind you'd expect only in anonymous cities.

Culpability translates this dynamic for the twenty-first century. The primary setting—a Chesapeake Bay beach house—becomes moral geography. Holsinger starkly juxtaposes the family's comfortable rental against the fortress-like compound of the tech billionaire next door. Noah, our protagonist, comes from a blue-collar background and narrates with a keen, chip-on-the-shoulder awareness of these socioeconomic fault lines. Here, privilege and technology define the landscape.

The craft lesson crystallizes: the midcentury ranch house, the family convenience store, the beach house dwarfed by the billionaire's estate—each location embodies the characters' economic reality and emotional weather.

Staying vs. Leaving: Character Arc Through Geography

The most powerful throughline, for me, was how each book interrogates the supposed binary of staying or leaving one’s hometown. One is not “better” than the other, though certain characters have a preference or even a primal need to escape.

In Bridge of Sighs, Lou Lynch is sixty years old and has "spent his entire life in Thomaston." Russo brilliantly explores, as one reviewer noted, "how a person can live a wide life in the smallest of ponds." His counterpoint, Robert Noonan, fled Thomaston when he was a teen and lived life as a famous artist living in Italy with shows around the world. Russo does not judge either character for their choices and we learn the secrets and motivations that made them stay and leave.

In Buckeye, most of the characters remain in Bonhomie through the postwar boom and the Vietnam era, watching their town metabolize change, bound by secrets and the stubborn gravity of family legacy. But Margaret has had enough of small town life after a certain point; she moves to the city, alone, and re-establishes herself while her husband and son are left to deal with the aftermath.

In Culpability, the characters face complex, complicated moral questions about responsibility and technology in their modest beach house in a rural area on the Chesapeake Bay. The looming presence of their next-door neighbor tech billionaire and a series of devastating events lead to one character’s choice to stay at home and not attend college.

Final Thoughts

These authors resist reductive narratives. Neither Lou's optimistic rootedness nor Bobby's Venetian exile delivers complete satisfaction. Similarly, in Culpability, Lorelei’s professional "success" with her AI program is shadowed by moral vertigo. The tech billionaire's "success" manifests as an isolating fortress. Home, like achievement, reveals itself as a complicated and often bittersweet internal state rather than a fixed coordinate.

Small town isn't a limiting descriptor—it's an entire cosmos. When rendered with specificity, economic groundedness, and hard-won empathy, the small-town novel becomes a profound meditation on how place shapes identity, how landscape becomes destiny.

The lesson here: staying isn't stagnation. It's a complex, active choice requiring constant justification—to yourself, to your family, to the idea of what your life might have been elsewhere. What the books make clear are people who escape their hometowns can't escape a sense of loss, and neither do those who stay.

In other words, geographic escape doesn't guarantee psychological freedom or a sense of belonging, or even success. Because this: